By Rick Suchow

(This article was published in Bass Guitar Magazine, February 2009 issue)

Back in the early Sixties when American music was in the process of being conquered by the British Invasion, and bands like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones were suddenly dominating the country’s pop charts on a regular basis, the U.S. was concurrently brewing up a storm of its own to answer back with. The sound that tornadoed out of Detroit, swept up American radio, and then blew back across the Atlantic, was known by a single word: Motown.

From a small house in Detroit nicknamed “Hitsville USA“ by it‘s owner Berry Gordy Jr., the “Motown Sound”, as it became to be known, would be as influential a force in popular music as any other in history. Hit after hit record cranked out of Hitsville’s Studio A inside the home of Motown Records at 2428 West Grand Boulevard: “Dancing In The Streets“, “Ain‘t No Mountain High Enough“, “Signed, Sealed, Delivered”, “My Girl”, “I Heard It Through The Grapevine”, and on and on. The artists that delivered these irresistible groove-heavy songs were suddenly influencing music acts everywhere. “Smokey Robinson was like God in our eyes," said Paul McCartney, reflecting on the Beatles’ biggest musical influence when the Sixties started taking shape. "The sort of people we were listening to then were on Stax and Motown; black American, mainly. I liked Marvin Gaye, Smokey, people like that. The Miracles were a big influence on us, where Little Richard had been earlier. Now, for us, Motown artists were taking the place of Richard."

Many of Motown‘s artists would become household names, and their songs a permanent part of music’s pop and R&B songbook. Yet the musicians who played on nearly all of Motown's decade long string of chart toppers-- garnering more number one hits than the Beatles and Stones combined-- were never credited on the albums, and remained virtually unknown to the millions who loved the music they played and bought the records they helped create. Though their story would eventually be told, this small group of Motown session players who called themselves The Funk Brothers would wait twenty years for worldwide recognition. Some of them didn't live long enough to hear the accolades, including the man at the heart of the the Motown Sound: bassist James Jamerson.

By the time he was thirty-five years old, Jamerson had not only played on more pop and R&B hits than any bassist in history, but his singular style on the instrument influenced an entire generation of players that followed in the trail he blazed. With an uncanny and unpredictable sense of syncopation, and the ears to create wonderfully melodic bass lines to compliment a song’s vocal, James Jamerson’s recorded performances were often bass masterpieces in themselves. “I didn’t know that it was James Jamerson”, said the Who’s John Entwistle many years later. “I just called him the guy who played bass for Motown, but along with every other bassist in England, I was trying to learn what he was doing.” McCartney fell under the Jamerson spell early on as well and called Jamerson his hero. “His style of bass playing for Motown was one of my major influences when I was learning electric bass. He’s one of the greats.” And no stranger himself to revolutionizing the bass guitar, Jaco Pastorius often cited Jamerson as one of his biggest influences on the instrument as well. Simply put, no one had a feel like James Jamerson.

Born in Charleston, South Carolina in 1936, James discovered his affinity for music early on in life. Learning to play his cousin’s piano well enough to perform at the local church by the age of ten, Jamerson also studied trombone in elementary school. As a teenager, he relocated to Detroit with his mother, who found employment in the city at the heart of the booming auto industry after her divorce from James' father. In 1954, while attending high school, James found his calling when he spotted an old upright bass laying on the floor in the back of the school’s music room. From that day on, James knew he would play bass for the rest of his life.

Jamerson’s ability on the acoustic-- which he called the “string bass”--quickly grew by leaps and bounds. He dove head first into the Detroit music scene, playing with blues players like guitarist John Lee Hooker and the locally popular Washboard Willie. Absorbing the influences of upright bass titans like Ray Brown, Percy Heath and Paul Chambers, Jamerson honed his jazz chops and found work with jazz musicians like Barry Harris and Yusef Lateef. His R&B side continued as well, and James soon participated in local jams and recordings sessions with regularity, his local reputation as the new bass phenomenon in town quickly spreading. Fortunately for Jamerson, Detroit was also the hometown of an astute businessmen/songwriter named Berry Gordy Jr., and during one of James' sessions fate intervened. While recording at Anna Gordy's studio, she and her husband Berry heard Jamerson's unique talent . “Berry heard the lines I was playing and fell in love with them,” James recalled in a 1979 interview for Guitar Player magazine. “He asked me if I'd be interested in coming over and being part of the company, and I told him yes.” Jamerson would continue playing sessions on upright for several more years, before reluctantly switching to Leo Fender’s then-recent invention, the electric bass. Although Jamerson’s first love would always be the upright, he realized that music trends were changing and would need to keep his sound current in order to work as much as possible. He bought his first electric bass in 1961 when singer Jackie Wilson asked James to join him on tour.

The acoustic to electric transition was fairly easy for Jamerson. “It just took a little while to get the feel of the neck, because the neck is smaller,” he said. “It took me about two weeks.” James applied much of his upright style to the electric (see sidebar), and with the amplified bass guitar the Jamerson sound was now an audibly clearer voice. This in turn inspired him to become even more adventurous in his playing, knowing that every note and nuance would be heard. After the Wilson tour, Jamerson continued to go on the road with various Motown acts until 1964, when Gordy decided that the Jamerson sound was too essential an ingredient in Motown's hit-making recipe to do without. In addition, artists like Smokey Robinson and Marvin Gaye insisted on using James for all their sessions, and soon Gordy decided to keep him permanently off the road and trenched in Motown’s “Snakepit", the Funk Brothers' nickname for Studio A. Berry simply could no longer hold up the Motown machine waiting for Jamerson's magic, and offered him a weekly salary to be one of the company's first staff musicians. Jamerson accepted and would keep the position for the next fourteen years.

In the studio, Motown producers would rarely tell Jamerson what to play, giving him the freedom to come up with his own creation. While an arranger's typical chart might have a short written bass line in the first few bars or even a verse and chorus, it was merely to give Jamerson the song’s basic groove, after which he would be on his own. Many times he would be handed nothing more than a simple chord chart, as he revealed in a 1983 interview with writer Nelson George: “Holland-Dozier-Holland would give me the chord sheet, but they couldn’t write for me. When they did, it didn’t sound right. They’d let me go on and on and ad lib. I created, man. When they gave me that chord sheet, I’d look at it, but then start doing what I felt and what I thought would fit. All the musicians did. All of them made hits. I’d hear the melody line from the lyrics and I’d build the bass line around that. “I always tried to support the melody. I had to. I’d make it repetitious, but also add things to it. Sometimes that was a problem because the bassist who worked with the acts on the road couldn’t play it. It was repetitious, but had to be funky and have emotion.”

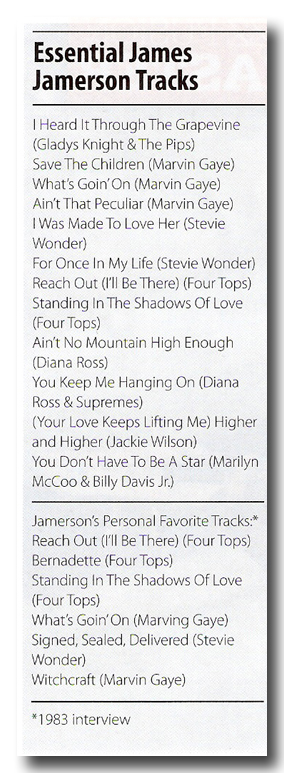

Jamerson’s funk and emotion would grace a tidal wave of smash hits throughout the remainder of the decade and on into the Seventies. By the time Marvin Gaye entered Studio A in 1971 to record his groundbreaking masterpiece album What’s Goin’ On, Jamerson’s playing was at a peak, and the resulting release went straight to the top of the charts. James' Precision bass seemed to simply explode out of the vinyl grooves that contained its sound, and resonated through radio stations across the land. What's Goin' On would not only become Motown’s biggest seller of all time and its most critically acclaimed, but also a benchmark for all bass players who took notice of the astoundingly innovative bass work driving it all. Jamerson's landmark four-string performances on tunes like "What's Goin' On" and “Save The Children“ remain some of the finest displays of bass brilliance ever captured on a recording. For Jamerson, it was not only a turning point musically; for the first time his name was credited on a Motown album, thanks to Marvin’s insistence, and the world was finally informed of Motown’s secret bass weapon.

By 1973 the company had moved its entire Detroit operation to Los Angeles, attempting to keep pace with their ever-growing business. Although Gordy had kept a small L.A. office for years, he now had one eye on Hollywood as Motown expanded into the film industry with a distribution deal for Lady Sings The Blues (starring the label's Diana Ross), and Gordy’s directorial debut Mahogany. While the company continued to prosper in sunny California throughout the seventies, the move west was not as easy for Jamerson. Suddenly finding himself in new surroundings and no longer playing with his Detroit studio mates on a regular basis, James often struggled with the L.A. scene. He had particularly missed drummer and fellow Funk Brother Benny Benjamen, who died a few years earlier from a stroke. While Jamerson's sheer bass talent and musical reputation still kept him busy during his first few years in L.A., adding his masterful touch to records by Joan Baez, Bonnie Pointer, Bill Withers and many others, James' darker side would begin to creep in. Alcoholism and personal problems slowly got the better of him and interfered with his work. Although his drinking habit began years before in Motown's Detroit heyday, he never allowed it to compromise his performance in the studio, and generally kept his partying contained to late-night jams or hangouts with his musician buddies. Now in his new life Jamerson began to lose the battle of the bottle, and with the music scene changing and James not always changing with it, his career slowed down as the Seventies came to a close. Health problems overtook Jamerson in the early Eighties, and for the most part he became a forgotten man. When Motown Records televised its much-hyped 25th Anniversary special in 1983 to millions watching around the globe, Jamerson’s name was never mentioned once in the telecast. Finally on August 2, 1983, James Jamerson died of complications from a heart attack at the U.S.C. Medical Center in Los Angeles at the age of 47. He left the music world in virtual anonymity, never knowing the level of fame he would eventually attain.

The interview Jamerson gave to Nelson George appeared one month later in the October 1983 issue of Musician magazine. It was part of a larger feature in which George told the story of all the unknown session musicians of Motown. The article, which Nelson titled “Standing In the Shadows Of Motown: The Unsung Session Men Of Hitsville’s Golden Era,” was barely over five pages in length, and Jamerson’s quotes only a few paragraphs, but it was an important and historical document in that no one had ever told the behind-the-scenes story before. George was intent on penetrating Motown’s corporate vail that hid the contributions of Jamerson and company for so long, and spoke with several of The Funk Brothers for the article. “Although it is hard to imagine contemporary bass playing without James Jamerson, I was only the second person to interview him at length,” wrote George. He seemed as frustrated by Motown’s failure to acknowledge the musicians as they did; “Even in their heyday," he commented, “they rarely received songwriting or arranging credits. While their Memphis counterparts Booker T. & The M.G.’s became darlings of the music world, the men of Motown toiled in anonymity.” While George’s article may have been limited to the readership of Musician, it was significant for another reason: it supplied both the inspiration and title for what would become the most extensive documentary ever on James Jamerson.

In the aftermath of Nelson George’s 1983 article, a guitar player named Allan Slutsky realized he had stumbled upon the title for his book-in-process of Jamerson bass transcriptions, which he planned to publish under the pseudonym “Dr. Licks”. Having previously published one book of guitar transcriptions years earlier, Slutsky titled his new book Standing In The Shadows Of Motown: The Life And Music Of Legendary Bassist James Jamerson. The book became an important turning point in Jamerson’s posthumous career, as Slutsky recruited 25 top bassists to record Jamerson’s bass parts for the book's accompanying two audio cassettes, including bass icons like Anthony Jackson, Chuck Rainey, Marcus Miller and Will Lee-- all admitted Jamerson aficionados. In addition, Jamerson's son James Jr. contributed, and Paul McCartney supplied the book's introduction. Slutsky smartly panned the bass track to one side and rhythm track to the other on each tune so that the listener could clearly hear Jamerson’s part isolated as they read along with the Dr. Licks transcription. He also expanded on Nelson George’s story, and with extensive research and interviews with the Jamerson family and surviving Funk Brothers, produced page after page of new insight into Jamerson's life. The success of the book eventually led to a feature film with the same title and a soundtrack CD, which earned Slutsky and The Funk Brothers a first-ever Grammy award.

In 2000, James Jamerson achieved his ultimate tribute. Along with the rest of the Funk Brothers, James was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame in their newly-created 'Sideman' category. It would be the most fitting achievement of all for a man who revolutionized his instrument, yet who was faceless and nameless to the millions who bought the records he helped create.

back to top

BGM Issue 41