(This article was published in the March 2011 issue of Bass Musician Magazine)

Harvey Brooks: Reflections On A Low End Legacy

An Interview With Rick Suchow

Years from now when music historians look back at the most influential artists of the 20th century, opinions will likely vary, but you can be sure that three names will pop up more often than not: Miles Davis, Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix. To the casual listener these three iconic figures may seem to be far apart musically, but at the very least they do share one common denominator: bassist Harvey Brooks played with all of them.

A deeper look into Harvey’s impressive resume reveals a long list of well-known artists who have utilized his abundant bass talent, including The Doors, Donald Fagen, Stephen Stills, John McLaughlin, Mike Bloomfield, Seals and Crofts, and countless others. In fact, beginning in the mid-sixties and spanning the next several decades, the name Harvey Brooks was one of the most recognized in the bass business.

Interestingly enough, Harvey Brooks wasn’t always Harvey Brooks. Born Harvey Goldstein, the New York native found his musical calling in his early teens, and soon established himself as a highly respected bassist who was adept in rock, blues and jazz. Playing the requisite New York club and lounge circuit, it was during a resort gig in the Catskill Mountains that Harvey decided to change his last name, a common tradition among bandleaders and musicians who often used stage names. Harvey’s big break came at the tender age of 20 when his good friend and fellow musician Al Kooper hooked him up with Bob Dylan. Brooks recorded Highway 61 Revisited with Dylan, joined his touring band, and never looked back.

As if being a first-call bassist in a booming rock music industry wasn’t enough, Brooks also became a producer at Columbia Records, where he suddenly found himself an office away from famed jazz producer Teo Macero. Harvey and Teo bonded quickly, and their friendship led Brooks to Miles Davis, who Macero often produced. Harvey landed the coveted spot as Miles’ first electric bassist and played on two of his albums, most notably the landmark Bitches Brew, which became the best-selling jazz album of its time. By 1970, Harvey’s place in recorded music history was secure.

The dizzying whirlwind pace of his first few decades as a pro eventually simmered down a bit, but Brooks remained an in-demand bassist and joined Donald Fagen’s Rock And Soul Revue in the nineties, backing Fagen and his high-profile bandmates Michael McDonald, Boz Scaggs, Phoebe Snow and others. In 2009, after a lifetime of laying down the low for a who’s who of American artists, Harvey and his wife Bonnie decided to relocate to Israel, where he still remains active playing sessions, concerts in Tel Aviv, and various other projects. He also hopes to bring some of his old friends to the country to perform there from time to time.

It was an honor for me to interview Harvey. I was not only eager to get his vantage point of working with some of the greatest artists of our time, but also hopeful that he would be willing to offer advice and share tips with all of us who do our best to make a living playing this instrument we love. Fortunately he happily obliged, and so I present to you a giant of bass history, Mr. Harvey Brooks.

Some might consider Dylan and Miles to be at opposite ends of the musical spectrum. From your perspective as a bassist, what were the similarities in the way you approached playing and recording with both of them?

Both Miles and Dylan created their music in spontaneity as well as constructed ideas. When I recorded with Dylan on Highway 61 and New Morning there were the minimal amount of takes. His performance and the overall feel were the determining factors of the master take. Tuning or mistakes were not as important. I didn’t really have much time to construct an actual bass part, I just played what felt right.

On Bitches Brew and Big Fun with Miles, it was all spontaneity. We had one rehearsal at Miles’ apartment, where we played for about a half hour and then he put on some Jack Johnson fight movies. The session was at Columbia Studios, we set up and Miles gave us our first direction:"This tune is based on a C tone center." He then directed individual players to start and stop on his command! There was no pre-conceived structure laid out for us, we had to create the moment. Miles used this technique on all the sessions, He and producer Teo Macero would then take what we did and construct the form that created cohesive structures and musical thoughts through the editing process.

Did Miles ever verbalize to you what he specifically wanted you to play? How did he generally give you direction with regard to your bass parts?

In my case, I was the first electric bassist Miles had worked with so he left me alone to fend for myself, except for one request, which was to keep it consistent on the bottom– which I took to mean keep the groove simple and leave the rest to him.

What, if any, was a typical recording session with Dylan like, and what was his process for working out his songs with you and the band?

Dylan was very much in charge. He made all the decisions and his manager Albert Grossman would be there as an adviser. Bob would play the tune a couple of times, and as he played we would sketch out the tune for the chord progression, the form and any special parts that related to our instruments. As soon as Bob was ready we had to be ready!

What was it like to be a musician in New York’s Greenwich Village in the mid-sixties?

After the Highway 61 sessions with Bob Dylan my reputation in the folk-rock world was established. I was called to play and record with many of the 1960’s contemporary folk artists such as Eric Anderson, David Blue, Judy Collins, Tom Rush, Richie Havens, Tim Hardin, Fred Neil, Phil Ochs and others. The central performance clubs were The Bitter End, Gaslight Café, the Café Au Go Go and Café Wha. I had an apartment on Thompson Street and the Au Go Go was around the corner on Bleecker Street, and I became the house bass player there. I would play with whoever was on the bill that evening, with no rehearsal and just a quick run-through backstage. So to answer your question, what was it like to be a musician in Greenwich Village in the mid-sixties? It was AMAZING!

What are some of the most memorable sessions you’ve played on, and what made them memorable for you?

Highway 61, which was my first recording session, an introduction into the pop music world and meeting Bob Dylan, which led to my first ever concert tour to Forest Hills and the Hollywood Bowl.

Soft Parade [The Doors]: Robby Krieger and John Densmore heard me with the Electric Flag and asked me to play on their Soft Parade album. The Doors were going through tough times as a band and my bass lines served as a bridge between unconnected sections as well as hooks for two of the hits on the album, "Touch Me" and "Tell All the People". Concerts at the Forum in LA and Madison Square Garden in New York followed shortly after.

Bitches Brew and Big Fun [Miles Davis]: When I was a producer at Columbia / Sony Records, producer Teo Macero had the office next to me and we became great friends sharing music and history. Teo was Miles Davis’ producer. Miles wanted to do a demo session with his wife Betty and wanted to use electric bass. After the session Miles told Teo to book me for the Bitches Brew sessions, and that was my door into the jazz world! I shared the bass chair with Dave Holland, traded rhythms with Jack DeJohnette, Lenny White and Billy Cobham. Miles took me to my next level.

Summer Breeze [Seals & Crofts]: My best lessons in songwriting were the pre-production work with Seals & Crofts for the Summer Breeze album. The tunes I remember playing, "Summer Breeze" and "Hummingbird", hooked me up with drummers Jim Keltner and John Guerin.

What, in your opinion, is the ideal way for any bassist to approach a recording session?

If there are charts, review them, write notes and cues that help guide you through the chart, and ask the conductor or leader of the session any questions you might have. If there are no charts make an accurate chart of the song. This familiarizes you with the song and any parts that are challenging. When rehearsing, pay attention to the drum part and any instrument in your range so as to construct a bass part that fits rhythmically and harmonically. And finally, come to the session with no preconceived thoughts or opinions. Let the music do the talking.

After establishing a successful bass career, you became a producer at Columbia Records. Did the experience of being a producer change your approach to playing bass in any way? Did it affect the way you heard, and interpreted, an artist’s material when coming up with your bass parts?

As a producer you get to hear the music with a magnifying glass. A producer is responsible for the music from the creation to the final mastering. I learned what happens to the recorded music as it moves through each stage and what happens to my bass sound along the way, so that when creating a bass part I’m also making sure my sound will hold up through the various editing processes. I learned to focus on the whole tune rather than just my part or the rhythm section.

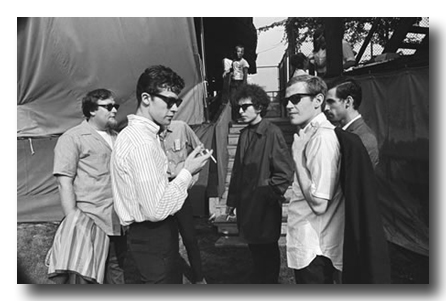

What is your memory of playing onstage at the Monterey Pop Festival with your group Electric Flag?

Monterey Pop was our first gig. We were pumped. Bloomfield kept using the word "groovy" in all its variations, in his excitement to describe the scene that was set out before us. We played in the afternoon so we able to see people dancing and the expressions on their faces as we played. Their feedback was amazing. The band was nervous and tense, but once we started performing and the audience accepted us we relaxed enough to play a decent set.

The party backstage was a hang with Janis Joplin and Big Brother & the Holding Company, Jefferson Airplane, Mamas & Papas, Jimi Hendrix, Simon & Garfunkel, Paul Butterfied, Al Kooper, Otis Redding, Booker T. & the M.G’s, Ravi Shankar, The Who, Grateful Dead, Hugh Masekela and the list goes on.

Who were your musical influences when you were coming up ( bass players or non-bass players)?

Paul Chambers, Scott LaFaro, BB King, Donald Fagen, James Jamerson and Chuck Rainey.

How did your gig with Donald Fagen and the New York Rock and Soul Revue come about, and what was it like being a part of it?

I was the bass player in The Little Big Band with Jimmy Vivino and Gary Gold at Hades in NYC. The Little Big Band was a 10-piece horn band that burned. Donald had previously recorded an album with other players including the incredible keyboardist and vocalist Jeff Young, who was also in The Little Big Band. Jeff brought Donald down to hear the band and Donald became a frequent jammer, and when the Rock and Soul Tour was put in place I got the gig. Playing gigs with Donald Fagen, Michael McDonald, Phoebe Snow, Boz Scaggs, Walter Becker and Chuck Jackson was an incredible opportunity to play great music.

In this era of CD’s being replaced by downloads, it would seem little attention is paid to album credits anymore, therefore less "free advertising" for session players. What advice would you give to bassists trying to get steady session work these days?

First, live in a hub where there is studio activity. For me it was New York City. Become a part of the music community and get involved with the business of music. Develop as many musical skills as you can. The more prepared you are to be spontaneous, the more you are able to take advantage of opportunities. Social networks put you out and about. Facebook, Twitter and blogging keep you aware of what is going on, who’s doing what, and where they’re doing it.

What is the music scene like now in Israel, and how does it contrast with the American music scene?

The main difference is that the Israeli music scene is much smaller, mainly because the country of Israel is the size of New Jersey. Be that as it may, there are very strong jazz, blues, pop and classical artists and players. A recording session that I recently worked on at DB Studios in Tel Aviv used the Tel Aviv Symphony string section, which would have been too expensive for a recording budget in the US but is budget friendly here. That says it all!

What sort of practice routines do you have on bass?

My warm-up routine usually consists of 4-finger chromatic movement up and down the neck on each string, shifting first up the neck with the 4th finger and then the 1st: 1-2-3-4 shift, 4-3-2-1 shift, 1-2-3-4 shift, etc. Once the 1st finger hits the 12th fret you reverse the pattern, shifting downward from the 12th fret: 1-2-3-4 shift, 4-3-2-1 shift, 1-2-3-4 shift, and so on. This stretches out my fingers and palm.

I also practice one octave scales on each string starting on the 3rd fret, for example fingering a major scale on one string as 1-1-3-4 on the 3rd, 5th, 7th and 8th fret, shifting to the 10th fret and fingering 1-1-3-4 on the 10th, 12th, 14th and 15th fret.

What gear do you currently use?

I use a Hartke amp, Labella strings, a TG fretless bass and a Fender Precision.

Looking back on your career, what is one thing you might have done differently?

After the Bitches Brew album Miles asked me to tour with the band. I declined. I had some other projects working and also felt a little insecure in the jazz idiom. I missed a great opportunity to expand my musical vocabulary.

How has your bass playing evolved over the years? How are you a different player now than when you were years ago?

My influences growing up consisted of rock and roll, blues and jazz, music that was based on instinct and immediacy. When I began to do session work after the Highway 61 Dylan album, I was expected to read music on some of the more structured sessions. I could read chord charts but not bass clef, so I had to learn to read. I began to acquire books on rhythm, scales, chords, composing, ear training and method books, and all kinds of fakebooks (books of tunes). At the same time that this literary musical awakening was going on, I was getting all kinds of sessions that were pure instinct, demanding only my heart and soul. No problem– I have always been a melodic player who could at the same time "keep it simple".

Over the years my ability to hear the music has evolved and my technique has grown to accommodate what I’m hearing. I’ve learned enough guitar and piano to harmonize the music and bass parts I compose. I’ve also been blessed with the most wonderful wife and partner Bonnie, who inspires me to create and continue to grow.

Rick Suchow: Bass

harvey brooks (march 2011)

-

(Mar, 2011)