by Rick Suchow

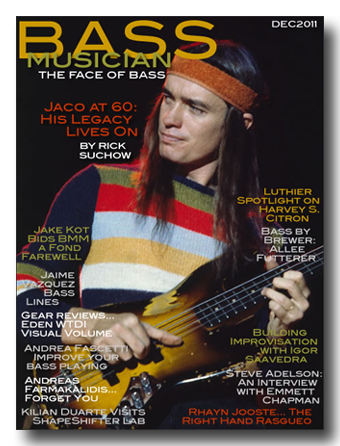

(This article was published in the December 2011 issue of Bass Musician Magazine)

“The first time you play, when you’re young and you realize that you’re actually playing, that you’re the one making it happen… to stay aware of that incredible energy and honesty, that’s what it’s about,” Jaco Pastorius once commented. “I take performing for granted, I don’t get nervous. It’s like my responsibility; it comes through me.”

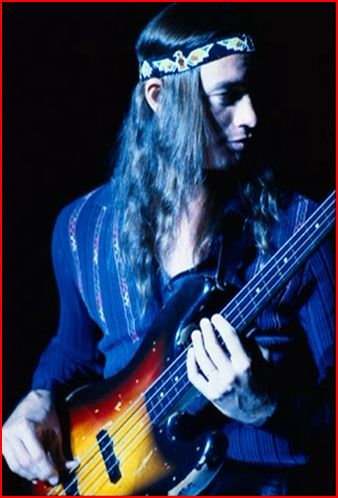

Certainly much incredible ingenuity came through the adroit hands of the legendary bassist, who would have turned 60 years old this month had his life not been cut brutally short in 1987. In his limited time on earth, Jaco completely revolutionized the art of playing electric bass, and did so in a way that has yet to be equaled. It’s certainly no exaggeration to suggest that when music historians list the singular musicians of the 20th century, Pastorius will stand with but a small handful of players– Charlie Parker and Jimi Hendrix, to name two– who emblazoned such an indelible stamp on their instrument that they permanently altered the course for all who came after. Perhaps it’s notable that none of those particular three greats lived to see their 40th birthday; who knows the price of true genius. Regardless, it’s tempting to imagine where Jaco’s journey might have taken him had he lived, and it’s certainly our great fortune that he left us with a brilliant rainbow of recorded performances, a remarkable discography that cements his place in music history.

Jaco’s contributions to the bass guitar still reverberate today. The road of discovery that all bassists travel – indeed all musicians— in search of self-expression in sound, is a road that is shorter for those who learn from the originality of Jaco’s imaginative approach. His success at breaking barriers and traditions that long constrained players of the same instrument remain an inspiration. Jaco described his own methodology, to some degree, in an interview for Melody Maker early in his career: “It was partly a conscious decision to stop listening to the latest trends,” he said. “I’d started to realize that what I was playing on bass guitar was very unorthodox, and in order to develop that further I figured I shouldn’t be listening to the latest hip bassists, whoever they might be. I never listened exclusively to bassists. I’m interested in music, period. And growing up in Florida, where there is no one musical clique that’s predominant, I’ve been able to study a great variety of styles.” Perhaps even more telling was this insight he offered to DownBeat: “Something happened to me when my daughter was born. I stopped listening to records, reading DownBeat, things like that, because I didn’t have the time anymore. That wasn’t bad; that’s why my sound is different. But there was something else. A new personality being born made me see that it was time for my musical personality to be born; there was no need for me to listen to records. I knew music, I had the makings of a musician, now I had to become one. My daughter made me see all this, because she was depending on me. I wasn’t going to let her down.”

In reflecting on Jaco’s storied career on this 60th anniversary of his birth, perhaps it’s his four-year collaboration with Joni Mitchell that remains the most intriguing. It was the well-established Mitchell who introduced Jaco to the larger pop music world when she first utilized the up-and-coming jazz phenom’s talents in 1976, helping to propel the Pastorius sound to millions.

More importantly, the two would create three masterful studio albums together. The trilogy of Hejira, Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter and Mingus was a creative milestone in Joni’s already distinguished career, in retrospect quite possibly her most important period. For Jaco it was a challenging musical setting far removed from the instrumental jazz and fusion that dominated his workload, and for Joni the trilogy represented a brilliant transition when the self-described “painter first and musician second” seemed to blur the lines that separated her two worlds of art and music. Her studio became more canvas than control room, her lyrics more abstraction than introspection, her song structures more brushstroke than traditional form. With a newly found confidence in both her voice and pen, Joni’s musical palette displayed new colors, and Jaco’s bass was clearly her favorite.

“She’s created a brooding instrumental sound that’s unique in popular music,” commented writer Stephen Holden in 1980, “a perfect sonic counterpart to her flowing, painterly imagery.” He referred to Mitchell’s newer sound as “stark, electric folk-jazz that’s centered on the protoerotic interplay between her own agitated rhythm guitar and Jaco Pastorius’ sweetly responsive bass.” With Joni, Jaco’s playing was filled with nuance and subtlety, and their collaboration was a fascinating musical conversation born out of trust, respect, personality and humor. The two clearly egged each other on to new experimental heights.”There was a real collaboration with Pastorius,” Holden later remarked, “in which his bass and her voice became a man-woman duet, an extremely intimate, deep dialogue between two musicians.”

“I had tried all along to add other musicians to my music,” recalled Mitchell in her documentary Woman Of Heart And Mind. “Nearly every bass player that I tried did the same thing. They would put up a dark picket fence through my music, and I thought, why does it have to go ploddy ploddy ploddy? Finally one guy said to me, Joni, you better play with jazz musicians.” Her search for that elusive bass sound ended when guitar player Robben Ford played for her Jaco’s head-turning debut solo album. “They were touring when my solo record had come out,” Jaco recalled. “He played her the album and she was knocked out. She just tried to get a hold of me, and that was it really. I just went and played. I didn’t even know anything about Joni Mitchell; I hadn’t even heard her music.” Joni used Jaco on four of the songs that made up her next album Hejira, including its stunning title track. “It was really fun coming in from nowhere and adding this thing,” said Jaco.”It was a nice combination. The cut ‘Hejira’, itself, I really like. I think that was the first thing I played with her.” That track is particularly noteworthy for Joni’s influence on Jaco’s studio technique, in which he emulated her fondness for layering multiple tracks of guitar. He mixed four separate tracks of his own carefully arranged bass parts, and at certain points in the tune had them all play back together. It was a technique he would use frequently with Mitchell, and with it Jaco again broke new ground, as multi-tracking different bass parts simultaneously was practically unheard of. The duo’s magnificent spectrum of guitars and basses was used to great effect on much of their work on Hejira and its double-album follow-up Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter. On Joni’s tune “Jericho”, for example, Jaco cleverly overdubbed combinations of bass harmonics to create beautifully stacked chord clusters.

This new phase in Joni Mitchell’s music had slowly begun to catch the attention of many outside her core audience, even if alienating some longtime fans who seemed to prefer the comparatively simpler arrangements and subject matter of her earlier work. Some critics as well were confounded by her seemingly dramatic turn, although admittedly critics can be easily confounded. Jaco, of course, was quick to come to Joni’s defense. “Fear,” he remarked, when asked about some negative reaction to her new music. “They’re limited in their thinking, listening or playing… a lot of people and critics who come to see her have listened to her first few albums — which I haven’t even heard– and they want to hear her like that because that’s where they’re comfortable. They don’t want to grow, but she grows and they put her down, you know? It doesn’t make much sense…a form of fear.” Of her newly found fans though, perhaps none turned out to be more important to Joni than the iconic jazz bassist-composer Charles Mingus, who admired the adventure in her new work. After hearing her Don Juan album, Mingus sought out Mitchell as a co-writer. Charles would hand Joni several of his uncompleted compositions to finish, which she eagerly did and recorded for the album she eventually titled Mingus. Once again Jaco was at her side, and the two assembled a stellar studio band for the recording of it, including Peter Erskine, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Don Alias and Emil Richards.

Soon after its release, famed jazz writer Leonard Feather asked Joni about her decision to use Jaco for the album, and if Charles was aware of it. “We talked about personnel and the people he suggested,” she explained. “I didn’t know any of them. I tried some sessions with people he suggested, but still, all the way along, in the back of my mind I had my favorites, and those are the people I ended up working with. You have to understand he was very ill then, so I couldn’t tell from his responses whether he knew Jaco’s work or whether he liked it. I couldn’t get any real feedback. All I knew was that he was very prejudiced against electrical instruments, but when he articulated his prejudices on a tape that I heard, Jaco transcends them all. He felt that with an electrical instrument you couldn’t get the dynamics; that the dynamics were all done by pushing buttons and so on. But Jaco completely defies all that; he gets more dynamics than any bass player… he’s phenomenal, he’s an orchestra. He’s a horn section, he’s a string section, he’s a French horn soloist — as a matter of fact when you have a job for the bass player, you almost have to hire a bass player!”

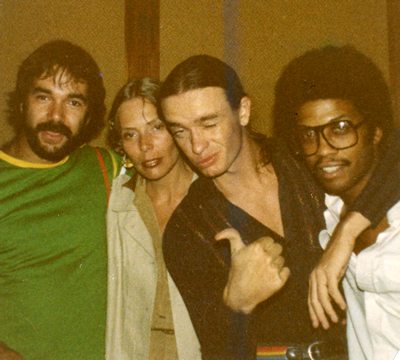

Drummer Peter Erskine recalls the Mingus sessions in his forthcoming e-book Written in Rhythm: an autobiography of Peter Erskine, chronicle of Weather Report and other bands. My sincere thanks to Peter for sending me the following advance excerpt from the book for the purpose of this article:

The Mingus album is memorable for many reasons, first and foremost because of Joni Mitchell. Joni recounts our first meeting in a book, describing how Joe and Jaco were athletically tossing a Frisbee inside the confines of an S.I.R. rehearsal studio and that, when the high-velocity Frisbee would be directed at me, I would shrink away in fear so as not to possibly jam a finger (much like my basketball/gym class in high school) — mea culpa for being a wuss, but now might be a good opportunity to explain that during my Little League tryout I got hit in the forehead by a line drive and have forever since been ball-shy — so, Frisbee-shy though I was, Joni took a chance on me drumming-wise. And I was, of course, a huge fan not only of Hejira but also of her earliest works, notably Blue, and feeling grateful for all of the lonely nights that music got me through.

Longtime producer and engineer Henry Lewy is at the helm in A&M Studio D. Add Jaco to this and I’m in heaven. Wayne will come in on the 2nd day to play with us and to overdub on what we would do on day #1. We recorded everything in two afternoons. The pianist at the first day’s session is British arranger Jeremy Lubbock. After we cut the first tune “Goodbye, Pork Pie Hat,” Jaco comes over to me and says, “Who is this guy? I’m going to call Herbie and see if he’s in town…” and so Jaco runs off to the telephone and calls H

erbie and essentially invites him to the session to take over. I seem to recall that Jaco got Joni’s blessings before or during this whole process, it all happened very quickly. The take with Jeremy was good and of course it’s awkward when he finds out that Herbie’s on his way … but by then it’s too late and so he leaves and Herbie enters … and promptly replaces the piano on the “Pork Pie” with Jaco smiling like crazy in the control room and we’re all smiling and now all in on the conspiracy, no regrets and full steam ahead.

We cut the rest of the album in fairly short order, a considerable achievement if not hasty, as the Mingus compositions are not the easiest songs to wrap one’s head around — these are the longest song forms I’ve ever encountered and I’m still not sure that I was up to the task. My contribution, if any, was to be a good anchor for Jaco. I also came up, unwittingly, with the rhythmic solution for the blues tune “Dry Cleaner From Des Moines” which was not enjoying much success as in its previously recorded be-bop form. Sitting at the drums between takes of another song, I started playing around with a beat that I first heard on a Gabor Szabo album that Bernard “Pretty” Purdie played drums on (an oddity titled Jazz Raga, the tune was “Walking On Nails”), but I was using brushes instead of sticks as Purdie had done. So, I’m just sitting there, amusing myself by playing and experimenting with this when Henry Lewy comes running out of the control room and yells “Don’t stop playing that! Keep playing that same beat!” and then he ran to get Jaco and we cut the basic track to “Dry Cleaner” in fairly short order — first take, as Jaco preferred — and the thorny question of how to record that blues was solved. Jaco wrote the horn chart and recorded it later at Tom Scott’s “Crimson Sound” studio in Santa Monica (former home to the Beach Boys’ studio, with lots of “hippie wiring” still extant by the time we were in there, according to engineer Hank Cicalo). That triplet ending? Jaco played it, as he had done for the intro, and just gave me a wink to cue me for the end.

However the album is judged artistically, I feel that it showed remarkable bravery on Joni’s part to put her imprimatur on this music in the midst or arc of her pop album career. Joni has great artistic integrity. The album also marked an interesting point in the use of electric instruments to play jazz, the Mingus collaboration putting a spotlight on the musical sensibility and aesthetic choices made with electric bass and piano — and the success or failure of that — and put a spotlight on the whole jazz meets pop thing that still resonates today. It’s not the easiest album to listen to but I give Joni high marks for it. As far as I know, it began her musical relationship with Herbie Hancock, and was also the starting point for the tour the following summer that would result in the Shadows and Light video. By the way, that was supposed to be Weather Report on that tour. Jaco had helped to set everything up and Joni and her management agreed to have Weather Report open the concerts with a set, to be followed by our backing her on the Mingus and other material. Well, as I begin planning for this great news I get a telephone call from Joe Zawinul.

“The Joni Mitchell tour thing is not happening. I told Jaco that he can do it because of his long association with her, but I don’t want Wayne or you to do it.”

“What happened?” I asked.

“I just told her we ain’t no fucking L.A. Express.” … click.

As it turned out, the 1979 summer tour did come together, albeit with a slightly different dream band that consisted of Jaco, Pat Metheny, Michael Brecker, Don Alias and Lyle Mays, with Pastorius serving as musical director. It would be the final collaboration together for Joni and Jaco, capping off a brilliant run of exceptional work. For the bassist’s fans at the time, the tour’s resulting live album Shadows And Light was a perfect complement to the previous year’s live Weather Report album 8:30, as the full array of Jaco’s talents in concert performance were now well documented for the world to hear. If there was still any doubt, his astounding sound and technique was clearly no studio-only phenomenon; Pastorius was, indeed, the real thing. Although Shadows and Light primarily featured Joni’s more recent material from Hejira and Mingus, it also offered an opportunity to hear Jaco’s clever interpretations of her older material, including “Free Man In Paris” and “In France They Kiss On Main Street”, among others. By 1980 the two had parted ways and moved on in different musical directions with their respective solo careers. Unfortunately for Jaco, that career would ultimately be a short ride; he was gone a few short years later.

So as we fast-forward more than thirty years to the present and look back from here, it’s clear that the musical bond between Jaco Pastorius and Joni Mitchell was lightning in a bottle, and that the unique recordings they created together have stood the test of time. For the uninitiated, now might be a good time to check out that brilliant trilogy of Mitchell albums; for those who already have them, perhaps a revisit with new ears is overdue. And finally–on this special occasion– for all of us players of the electric bass who continue to hone our craft, and strive to find ways to express ourselves with originality, let’s raise our collective glass to the man who did it better than anybody. Happy 60th birthday, Jaco… wherever you are.

I’d like to acknowledge the following sources for this article:

Cover photo by Dave Suarez; young Jaco photo courtesy of Bob Bobbing; Jaco with Joni, Peter & Herbie courtesy of Peter Erskine, from the Peter Erskine private collection; Peter Erskine photo courtesy of petererskine.com; Jaco onstage photo by Bob Powell, courtesy of Ingrid Pastorius; Joni & Jaco collage by Rick Suchow. Jaco quotes: Melody Maker 1976 (Steve Lake, writer); Musician 1980, (Damon Roerich, writer); DownBeat 1977 (Neil Tesser, writer). Joni quotes: DownBeat 1979 (Leonard Feather, writer); Woman Of Heart And Mind (Joni Mitchell documentary DVD). Stephen Holden quotes: Rolling Stone 1980, Woman Of Heart And Mind; Peter Erskine book excerpt: Written in Rhythm: an autobiography of Peter Erskine, chronicle of Weather Report and other bands. Special thanks to Peter Erskine, Ingrid Pastorius and Dave Suarez for their correspondence and contribution to this article.

***November 29th, 2011: It is with great shock and sadness that I must include the following unfortunate footnote: Ingrid Pastorius passed away yesterday, suddenly and unexpectedly. She and I corresponded several times over these past weeks regarding my article, and she was greatly looking forward to reading this story that she contributed to. I will include some of her thoughts and correspondence in my next article for Bass Musician. My sincerest condolences to her sons Felix and Julius. — Rick Suchow

Rick Suchow: Bass

jaco at 60: his legacy lives on...

-

(Dec 1, 2011)