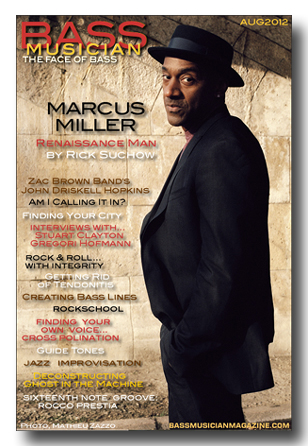

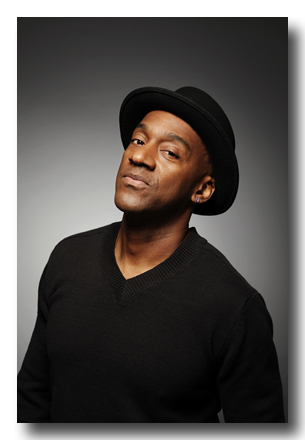

Marcus Miller: Renaissance Man

(Published in the August 2012 issue of Bass Musician Magazine)

“The thing that’s important to me now is to consolidate the different components of my musical life,” says Marcus Miller in a thoughtful, somewhat philosophical tone. “Up to this point they’ve been really separate. I mean, there are people who know me as a film composer who don’t even know that I make records, so they don’t know what instrument I play.” He says it like a musician with a renewed purpose; a man with a clear vision of the road that lies ahead and how he will choose to travel it.

He continues the thought. “There are people who know the Luther Vandross stuff who don’t know anything about Miles Davis or David Sanborn, you know? It’s just… I lead very separate lives, in all the different areas. And it’s worked for me, but right now I’m starting to decide that I want to introduce the Luther people to the Miles people, to the Marcus Miller solo artist people, to the film people. Try to find ways to integrate the whole thing. Maybe do a soundtrack for a movie where it’s really done as an artist, as opposed to just a film composer; something like that to bring things together. That would be interesting to try to do.”

It’s hard to believe that there’s anyone left who doesn’t know who Marcus Miller is. He’s a two-time Grammy winner, has appeared on over 500 albums as a sideman, has composed and produced ten critically acclaimed solo albums, and has been considered one of the best bassists on the planet for three decades. So when he tells me that some people in the industry don’t even know what instrument he plays, I find the idea completely foreign.

I should point out that this was not the beginning of our conversation. In fact, we’re winding down after nearly an hour, and it’s been a fascinating discussion. Yes, we’ve been talking bass of course, that’s a given. But our subjects have been bouncing around, covering a spectrum far wider than just talk of a few low-pitched strings on a slab of wood. For example: the day Miles passed away. The origin of the African American race. The tricks of transferring music onto vinyl back in the day. The starting five players Marcus wants on his basketball Dream Team.

But most of all, we talk about his new album Renaissance, because I’ve been listening to it for two solid weeks and I’m still stunned by its brilliance. The album, which seems to have taken up permanent residence in my car’s CD player, has been transforming my rather routine daily car ride into a traveling sonic adventure. Renaissance may be Marcus Miller’s finest solo album to date; it captures your imagination, kidnaps your soul, and drives one long-ass spike of funk through your gut for good measure.

Let me back up for a moment. A few days prior to my interview with Marcus, I find myself in Colony Music on 49th Street and Broadway, an easy 10-block walk from my apartment. The store sits in the heart of Times Square, a section of town that, even with its long tradition of glam and glitter, has seamlessly transformed even brighter into 21st century Big Apple, replete with giant block-long billboards, plasma screens, and cutting-edge eye-candy neon. Underneath it, at street level, are new pedestrian-only swaths of Broadway, bicycle lanes and tourist-friendly chairs and tables. And here, in the middle of it all, is old Colony Music, like a relic of old New York, virtually unchanged in its 60-year history. I’m inside the somewhat crusty shop, flipping through their vinyl record bins–yes, vinyl record bins–perusing the jazz and R&B sections filled mostly with records from the eighties. I realize, as I’m caught in this odd time warp, that the store’s vinyl collection strangely resembles my own, and I’m reminded that during that decade Marcus was everywhere. Album after album, artist after artist, jazz, funk, fusion, R&B, you name it… there he was. Back in those days, when album credits were a musician’s calling card, the name Marcus Miller was as inescapable as the sound of his funky Fender bass. Equally impressive is the fact that at the start of the eighties Marcus had been hand-picked by a re-energized Miles Davis to play in what would be the jazz legend’s comeback band; by the end of the decade the bassist had already produced, written and helped redefine that important stage of Miles’ career with albums like the landmark Tutu and the movie soundtrack Siesta.

By the nineties Marcus had established his own identity as a solo artist, and would go on to release a stellar string of solo albums carving out his unique brand of music. He had his own sound, his own style of composition, his own musical vision… practically his own genre, it seemed. It was, and still is, a rare talent not unlike that which Miles had. There are parallels in the careers of both men, Miles Davis and Marcus Miller, but I don’t bring this up to Marcus when we finally connect for our interview; I already know he’d be too humble to allow me to suggest any notion of that idea. Yet the parallels are there regardless, and here in 2012, just like Miles did with Marcus and Mike Stern and Bill Evans (the second, not the first) thirty years ago, Marcus has surrounded himself with a bunch of young and hungry musicians fired up, playing their butts off, and inspiring the musical creation that is Renaissance.

In a recent press release for his new music, Marcus explained, “I feel like a page is turning. The last of our heroes are checking out and we are truly entering a new era. Politically, things have polarized and are coming to a head. Musically, we’ve got all these cool ways to play and share music – MP3 files, Internet radio and satellite radio– but the music is not as revolutionary as the media. It’s time for a rebirth.”

The rebirth has apparently begun. While Renaissance is instantly recognizable as a Marcus Miller outing, from the very first bass-slapped notes of the opening cut “Detroit” to the unaccompanied final track (a cover of the Jackson 5′s “I’ll Be There”, where Marcus references parts of the original song’s vocal, rhythm and string arrangements on one bass simultaneously), there is a fascinating shape-shifting taking place as each track unfolds and the members of the band contribute their own talents. Renaissance is an album that is searching yet grounded, inspired in its reach. Tunes like “Nocturnal Mist”, “Revelation” and “Goree” are dark and earthy, while others like “Jekyll and Hyde” and “Mr. Clean” weave and punch. Of course, the bass playing is unmistakably, unshakably Marcus, but compositionally the music presents a previously unheard tapestry; it’s a look back and a look ahead at the same time, winking at the past as it maps out the future. And it’s still Marcus’ own genre, and still evolving. Backed by a band of relative newcomers Sean Jones and Maurice Brown on trumpet, Alex Han on alto sax, Louis Cato on drums, Adam Agati and Adam Rogers on guitar, and keyboardist Kris Bowers (along with keyboard veterans Federico Gonzalez Pena and Bobby Sparks), Renaissance may just well be a defining album in the long career of a remarkable artist; it just may be Marcus Miller’s renaissance.

I have a lot to ask you about the new album, but I want to mention a few Miles Davis things first. You just played at a tribute to Miles a couple of weeks ago at the Hollywood Bowl. You performed with your band Tutu Revisited, and a few other bands played as well. What was that whole day like?

The first thing they did was have a little ceremony in the early evening where they unveiled the Miles Davis stamp. It was like a life-sized version of it, which was really nice, and a couple of people said some words. It was very nice, and the concert was a beautiful night, man, because a lot of the guys who were there had played with Miles at some point or another.

Jimmy Cobb, who played on Kind Of Blue, was there with his band.

Yeah, Jimmy has been touring for the last couple of years with his group called the So What Band, and they basically play all the music from Kind Of Blue. Jimmy is the last guy, the last surviving guy from that band. And his band sounded great, man, they had Jevon Jackson on tenor, Larry Willis on piano.

Speaking of the original Miles Davis album Kind Of Blue, your cousin Wynton Kelly played on it.

Yeah, Larry was trying to do the Wynton Kelly thing! I mean, of course it’s like almost an impossible thing to try to do.

So obviously between your cousin and you, your family blood line is firmly in Miles Davis’ history.

Yeah, people weren’t even that impressed in my family when I was playing with Miles.

At the Hollywood Bowl tribute, there was also a performance by the Miles Electric Band.

Right. Vince Wilburn, who is Miles’ nephew and played with Miles in the eighties, put together a group where they kind of reflected the seventies Miles, you know? They had an incredible group too, man, they had Blackbyrd McKnight on guitar, Darryl Jones played bass, Badal Roy, Munyungo Jackson and Mino Cinelu all on percussion.

Mino played with you back in the eighties with the We Want Miles band.

Yeah, Mino was in the band I was in, exactly.

So it sounds like the Hollywood Bowl tribute was a great night.

It was beautiful. The best thing was to see is that Miles’ legacy is so strong. When Miles first passed, it was a little disappointing for me and a couple of the other guys who were playing with him, because in the US it didn’t seem like they were making a big enough deal out of it, you know? I remember back then one of the guys in the band said, “Man, they’re making a bigger deal out of George Burns”, who I guess had passed around that same time.

Yeah, I kind of remember it was just a news item.

Yeah it was a news item, but you know in France, man, it was like a national day of mourning.

As it should be.

As it should be. So anyway, the good thing is that over the years it’s gotten stronger and stronger, and dedicating a stamp to Miles is a nice thing, it kind of acknowledges that he’s really an American icon. I think that’s important.

A far as leading a band, what were the important lessons you learned from Miles that you apply to your own bands today?

I don’t think I’ve applied any lessons consciously, but I know that I do really try to get the most out of the guys in the band and really try to give them some space. I think if you frame it right you can really teach an audience about improvisation, and show an audience how a guy is improvising right there in front of them, making things up. There are things you can do in terms of the way you direct the band, you know, where you point at a guy who wasn’t expecting you to point at him [laughs], and say solo now. The audience goes wow, man, doesn’t look like he was ready for that, let’s see what he does, you know? And the next thing you know, this guy’s creating something beautiful, and I think Miles had a big influence on me in terms of making sure that you present your band well.

How did you go about picking the guys that you’re working with now, such as Alex Han and Louis Cato?

I first met Alex at Berklee a few years ago during a weeklong seminar I did there with some students. I was working on some music with them and we put on a concert at the end of the week. And Alex just stood out, man, I mean they were all great but he just stood out. I was like, who is this kid? He’s got rhythm, he’s got technique, he’s got inventiveness, he’s got the whole package. So I asked him to do a few things with me that summer and then waited for him to graduate. He had a year to go, or a year and a half to go, something like that. And after that, he started working in the band, and he suggested Louis Cato, who’s the drummer.

Right.

I said look, find me somebody that you like, you know, because what I was doing at the time was Tutu Revisted, which is a project where I went back to this music I had written for Miles 25 years ago, and was reinterpreting it. And in order to reinterpret it, I wanted to get really young guys who would bring a fresh perspective to that music. I already had Alex, so I said find me a drummer. He found me Louis, and eventually Louis recommended this guitarist Adam Agati, who’s on the new album. Then we found Kris Bowers, who won the Thelonoius Monk competition last year on piano and who was amazing. Federico Pena had been playing with me for a couple of years, maybe four years now, and he’s also a great keyboardist. So I had a nice group of really talented, really spirited, passionate cats. I was on the road with them on the Tutu Revisited thing, and I’m thinking, man, look what they’re doing with this music from 25 years ago, I should write something specifically for these guys. We should do an album that features the sound of this band, so that’s what Renaissance really is.

To me, the music on this album is more varied, at times a little deeper than some of your earlier stuff. You made the comment that you’re focusing less on production and more on composition. Is the writing part of your creative process something that’s becoming more intriguing to you, or more important?

Well, it’s always been important. But the emphasis sometimes shifts between the more rhythmic stuff, where it’s important to just have this groove going on, to writing more from the harmonic sense or the melodic sense, you know? When I was working on the Tutu Revisited stuff, because it was no longer the eighties, I really didn’t want that music to have synthesizers and drum machines, I really wanted it to be more organic. And because it was more organic, we really got to focus on the compositions that I had done for that album. When Tutu came out, a lot of people didn’t really get to key in on the composing for the album because the sound was so unique, you know, they just heard the sound. They didn’t really listen underneath the sound to hear the composition.

Right, and I remember when that album came out how revolutionary it was because of how you humanized all those electronic instruments. It didn’t sound synthy to me, I thought it was amazing that you were able to make it all sound so human. So I see your point about the compositions taking a back seat.

Well you know I didn’t even realize how much technology was playing a part when I was making that album, because I was part of that era and that was just what music sounded like [laughs]. You know what I mean? To me, it was just a very organic sounding album. I mean, I listen to it now and realize, yes, technology played a huge part in it. On Tutu Revisited it was nice because we were just playing the songs, you know, and it really kind of re-energized me in terms of composition. So I think when I went into this Renaissance album, man, I was really like, you know what? This is just gonna be about the band, about great performances, and me writing the best stuff I can come up with.

Let’s talk about some of the tracks on the new album. Besides your own writing, I think you picked a really interesting choice of cover tunes, some great ones. One of my favorites is “Tightrope”.

A ha ha.

You know something, I was looking at the track list but only kind of glanced at it at first. So I see the title “Tightrope”, I see that Dr. John is featured on it, and I just assumed it was the old Leon Russell tune.

A ha! Right.

You know? Because it just seemed like, okay, Dr. John is gonna sing that tune. But then I realized it was the Janelle Monae song, and your version of it just kills from start to finish.

The Janelle Monae song has a lot of New Orleans in it, you know what I mean? I mean that bass line, at least when I heard it on the radio a couple of years ago, I was like, man, that’s got a little boogie woogie thing to it, a little Professor Longhair on it! I really wanted to highlight that. I wanted to bring out the New Orleans flavor in that song because I heard it in the original, but it wasn’t really accented. So I figured Dr. John was a great guy to get involved. I called him up and I told him I needed him to rap. [laughs]

Yeah, he’s doing the Big Boi rap that’s on Janelle’s version.

I said to him, “You don’t have to make a rap, I just want you to do the Bog Boi rap”. So we had fun.

There are a couple of tunes on Renaissance that have almost a Weather Report-ish feel to them, such as the melody in “Redemption”. Did you have that melody in your head? Or was that something you composed on the piano?

I wrote it at the piano, playing the chords and singing the melody. And the song is about searching for the things about you that are special, even though they might not be obvious to you when you’re in a down period, or not feeling great about yourself. So it’s really about encouragement. The bass line is just pushing, encouraging (Marcus sings bass line). And the melody is searching. That’s why you’ll hear a couple of notes that sound a little different in that melody, notes that you might not expect.

Yeah, it really kind of twists and turns.

Yeah. I wasn’t really thinking Weather Report, that didn’t occur to me. But I was hanging with Wayne Shorter for a while when I was working on the music, so he might have had an effect on me while I was writing that.

You mentioned that the song “Goree” was inspired by a visit you took to an African Island, which I guess is called Goree?

Yeah, it’s off the coast of Senegal. It’s a little island about a 10-minute ferry ride off the coast of West Africa. It’s a small place, but they used to have a house there where they would keep the slaves to check them out health-wise before they sent them across the ocean into slavery in America. And they’d spend about three months kind of stacked on top of each other in these small rooms like cattle, you know what I mean?

Oh my god.

And they’d basically fatten them up, make sure they were ready to go, and then they would put them on this ship, man. And the slaves probably didn’t even know where they were going, but that was the last time they saw Africa. And that was kind of the beginning of the African American race right there, at that house that we were in. I mean, there was more than one house, but this one was representative of it, so you can imagine it’s pretty emotional.

Wow, that’s a horror.

Yeah, it was tough man. And then, I saw a picture of a slave ship with the Africans on it, and they were all really young. It didn’t occur to me that they were that young. They weren’t sending 25-year olds, they were sending, you know, 13 to 14 year olds, because once they got to the new world they were a ripe age. So it was a bunch of kids on there. So that song is about that, but it’s not just about despair and sadness, it’s also about the hopefulness that we can transcend that history, and, you know, we have. We have been transcending it and will continue to do so. So it’s about the hopefulness as well.

So from a writing standpoint, how do you tap into yourself deep enough to transfer that emotion into a composition?

Well, I had this melody, the first three notes of the bass clarinet melody that the song starts with. I had those in my head for a long time, and it always made me feel somber. But I didn’t really have anything to connect it to, you know. I tried to use it in a movie once. But when I experienced this thing on the island, those three notes came to me, and this time it was really much more complete because I had the emotional support for it. And when you write, you write something and then the next note is whatever seems like the logical answer to what you just wrote. So once you get going it kind of does it on its own.

You play some great bass clarinet on “Goree”, but bass-wise, it sounds like you’re starting out on an upright and kind of morphing into a fretless.

That’s exactly what I did. I started off on the upright because it starts off with a traditional sound. It’s a horn, an acoustic piano, the drums and the acoustic bass. But then when it morphs into the more hopeful part of it, the bass starts to move a little bit more and it starts to dance, and that’s when I switched to the fretless.

Your solo piece that closes the album is the Jackson 5′s “I’ll Be There”. You know, I can see bass players everywhere pulling out their axes and trying to learn that note for note. How long did it take you to come up with that?

Not that long. I was doing a bass clinic in France, and they said there won’t even be a drummer, it’s just gonna be you. So I said, well, I should probably come up with something that I can play on my own. And Michael Jackson had just passed, so I worked it up that afternoon to play that evening, and I mean, I played it and that was it.

You did that in one day?

Yeah, yeah. And then as I was doing this album somebody played me a tape of that clinic and said, remember this? And I decided it would be a nice way to end the album.

It’s beautiful.

It’s really, you know, the melody and the bass line at the same time.

And a lot of Michael’s little vocal inflections.

And the vocal stuff. But that’s how I hear a lot of music anyway [laughs], the top and the very bottom.

Did you ever work with Michael?

No, never worked with Michael, and kind of enjoyed just being a fan, enjoyed what he was doing.

I know you’ve talked about how the Jackson 5 was a big influence on you, as well as some of the old soul bands. Which brings me to your cover version on this album of War’s “Slippin’ Into Darkness”. What made you pick that one?

You know, there are probably about ten songs from the seventies that kind of formed my platform, my basis, like when I’m walking down the street one of those bass lines is gonna be playing in my head. And “Slippin’ Into Darkness” is one of those bass lines. The seventies were like the era of definitive bass lines, on a lot of songs the bass line just carries the song, and that’s just one of them, man. It’s just all about that feeling. I hadn’t heard that many people do the song, so I thought it would be nice to open it up and see what we could do with it.

Did you ever consider putting vocals on it or did you just have it in your head that it was going to be an instrumental?

I thought about it, but then I thought, you know, I’m really trying to stay with the band on this one. I really wanted to see what we could do to sound like we’re singing with our instruments.

The tune “CEE-TEE-EYE” is obviously a tip of the hat to the old Creed Taylor produced albums of the seventies. I know that Grover Washington’s “Mr. Magic” was a big album for you. What were some of the other old CTI records that were big for you?

Let’s see, there’s one by Deodato that was big, I think it was the one with his hit “2001″.

Right, that had Stanley Clarke and Ron Carter both on it.

Exactly. That was a big album for me. Ron Carter had a couple of them, All Blues and Blues Farm. Hubert Laws did a couple. The Grover Washington albums I loved, Stanley Turrentine had some great ones. Bob James had some beautiful albums on CTI.

What I liked about CTI was that you could tell the guys got together, had an arranger who would come in, write an arrangement, call the guys, and they put it all together pretty quickly. So you really got to hear the raw musicians. But in contrast to that, the album packaging was just so beautiful, man. Even if there was only one LP in the package, it was usually a dual cover, meaning the cover had a flap that you opened up and you could see the artwork, and it was really nicely done.

Funny, a lot of those guys on CTI, you wound up playing on their records later on in the eighties, like Grover Washington Jr. and Bob James.

Man, that wasn’t lost on me! [laughs] I remember I was playing with Grover on a track called “Just The Two Of Us”, which was a big hit with Bill Withers singing on it.

Of course.

But I remember in the vamp, it almost felt like I was playing along with a Grover Washington Jr. album like I had done a couple of years before, and the thing that woke me up was when I played a lick up high at the end of an 8-bar phrase. When I went back to the bass line, Grover carried that line that I had just played into his solo! And I never had Grover react to me, because when I’m playing along with his records he doesn’t really react! [laughs] But to be in the session, man, to be actually a part of that, was a real beautiful experience for me.

Was it intimidating?

You’re intimidated when you’re walking in the door, plugging in your bass, making the introductions. But once the music started, the music was just too important, you know? I lost that sense of being in awe because I was too busy playing, and too busy enjoying playing.

Right, you’re in the moment.

In the moment.

I was looking through all of these old vinyl records at Colony Music the other day, including some of those old CTI albums. My whole vinyl collection is packed in boxes and I haven’t listened to them in years. Where is yours?

Same place yours is, packed in boxes. But you know, I just got a turntable so I’m gonna start playing them. You just have to remember to return back to the turntable to flip the record over!

Right, forgot about that. And it skips occasionally too.

But it was tripping me out man, because as a producer, there were so many considerations about vinyl. One of the big considerations was that you wanted your album to have good volume, because if you remember, you had that turntable with the spindle and you used to stack the LPs one on top of the other, waiting to drop down onto the actual turntable. And so if your album was number three on somebody’s stack you didn’t want yours to be softer than everybody else’s volume-wise, so it was really important to have good volume. But you had to be careful because if you made the song too loud on the vinyl, it would cause the needle to jump out of the groove and the record would skip. So there was a fine art to getting your record as loud as you could without making the needle skip.

And plus, you couldn’t really go over like 45 minutes with the album.

We had to add up the timing for every song to make sure that it could fit on the vinyl, and the more time you had, the closer the grooves had to be together. But the closer the grooves had to be together, the less loud you could make your album. So we used to do tricks like make the first song really loud, because that’s the one that’s gonna be compared to the album that preceded it, right? You make your first song really loud, and then each song goes down a db [laughs], so you could fit it on the album without having a problem. So it was a whole culture of getting music onto the vinyl that doesn’t exist anymore.

Back to the new album, a really nice choice of song is “Setembro”, the tune Quincy Jones recorded. I don’t know much about Gretchen Parlato, who’s singing on it.

Gretchen is based in New York, and she’s really one of the premier New York jazz vocalists. I think she might have won that Thelonius Monk competition, or came in second, a few years ago. She’s very creative, very active on the scene. She just did a concert at Carnegie Hall with Lionel Loueke, who’s the guitarist from Benin, Africa. She’s always doing interesting things, and has a couple of beautiful albums on her own. And she did a great job on Setembro.

Yes she did. Did she know that Sarah Vaughn was singing on the original?

No, no, I didn’t even know that. The only version I heard was with Take 6 on Quincy’s version.

Right, that version. Take 6 is on it but Sarah Vaughn is also.

Man I didn’t even know that! So I gotta go back and check it out now.

But Gretchen sounds great on your version.

Yeah, she sounds beautiful. And we put an Afro-Cuban slant on it, even though it was written by Ivan Lins, who’s a really famous Brazilian composer. And I got Ruben Blades to collaborate, so it was nice because we found a different angle to approach the song from. Ruben came to the thing with a lot of passion, he had ideas, and it was a really nice experience.

Obviously you’re playing your fretless on this tune as well. What year is your fretless?

I think it’s a ’66. I have two 60′s fretlesses, but this is a ’66 I believe.

Your ’77 fretted, which I’d say is world famous at this point, should be in a museum one day. [Marcus laughs] Did you buy that new or used?

I bought it new in 1977 on West 48th Street in New York.

Which place? Manny’s? Rudy’s?

No, man… okay, I don’t remember the name of the place, but it was on the same side of the street as Manny's and Sam Ash, but a little bit west. It was on the 2nd floor.

Do you remember what you paid for it?

$265 with the case.

Really! I would say that’s appreciated in value a little bit, right?

[Laughs] Yeah, that was a long time ago, man. I had one that my mom bought me in ’75, but I left it on the side of my car and drove away, so I lost that one. Then I lost a second one about three months later, just being an airhead. And the third one, she went to the bank, you know? $265 was like maybe $1000 bucks now. The third one I managed to hold onto.

And that’s the one you’ve been using ever since, right?

That’s the one I’ve been using, yeah.

Let me ask you about the current studio scene. For guys coming up, it’s a lot tougher these days. There’s not as much work, and with everything being downloaded nobody even thinks about album credits anymore, you know? Back in the day you just put the guys’ names on the back of an album and that sold the album.

Yeah, yeah, that’s true. It’s a whole different thing now and I wouldn’t even call it a studio scene, because it’s not much of a scene. You do things from time to time. But for me the scene was waking up at 8:30, getting to your jingle at 9:00, doing a jingle from 9:00 to 10:30 and then another one from 11:00 to 12:30 and then doing a record date you know, for like Bob James from 1 to 7. Then doing another one at night from 8 to 12, you know, for whoever. That was a scene. Every day. And then on the weekends running over to NBC and doing Saturday Night Live. So that was my life.

Yeah, man.

And it was like you didn’t know who you were playing with, you didn’t even care. You just showed up at the studio, you know, and it could be Frank Sinatra, or it could be Billy Idol. It didn’t matter. You were just ready for anything.

What advice would you give to guys now trying to break into doing session work?

Well you just gotta really keep your eyes open, because it’s gonna happen differently for you than it happened for another guy, you know? The way I fell into studio work was because it was there, I was playing in bands and somebody called me for a studio date. They realized I could read music, and the next thing I know I was doing my thing. So who knows, man, if I hadn’t taken that one gig where somebody came to the club and heard me, it may never even have happened. I just tell everybody keep your eyes open and you never know where that opportunity is gonna be. If you get hung up on money, or this gig doesn’t pay me enough, you might miss out on a big opportunity. So you kind of have to keep an open mind.

So you’ve been at this for some 30-odd years, whatever, non-stop. Have you ever considered taking some kind of break?

Well for me, I’ll spend three months producing an R&B album, or I’ll spend a couple of months composing music for a movie, so they feel like breaks. And then I’ll go on tour and I’ll have to get my chops back up, because I was sitting behind a mixing board for the last couple of months. So I never feel like I’ve been doing the same thing over and over again, as a matter of fact, it feels pretty varied to me.

Are there any tunes on Renaissance that came out totally different than how you originally heard them?

Let’s see. “CEE-TEE-EYE”, I wasn’t sure what that was gonna be. I had the melody, I had the bass line, but I left it pretty open. And I was very happy with the way it came out, because it has that CTI feel, in that it wasn’t that structured, it just happened. It was the day we met Kris Bowers. Somebody recommended to me this young 22 year-old cat on piano, and so he came in and we started playing that song, and he killed it. It really kind of created a vibe for the song, so I’m really happy with the way that came out.

“Mr. Clean” is another great cover tune you did.

We were on the road with Tutu Revisited and we had a day off so we went to the rehearsal space and spent all day on that one song. You can tell because it’s got all these little quirks in the arrangement that you do when you have too much time on your hands. [laughs] You know, let’s put this in there, let’s do it this way the first time, but the second time we’ll do it a different way. So it’s one of those tunes, but I enjoy it because it kind of represents the community of our band working on an arrangement.

Right. And you’re gonna be taking this band out on the road?

Yeah, we just finished six weeks in Europe which was really nice, and then we’re going to Africa, we’re going to Japan, and going to the United States in September. We’re gonna go all over, man, so I’m excited. This is the way you have to do it now, you’ve really gotta put your boots on the ground and get out there, so we’re going to present this music to people. It’s been beautiful, man. We were playing in Europe before the album even came out, and people had that look on their faces like they knew the songs already.

As far as your equipment and technical information, you have a ton of stuff available on your website so I’m not going to get repetitive with all of that, but have you made any recent changes to your rig?

On this last tour I used EBS, and they had a new Fafner head that’s pretty awesome. In terms of pedals, my pedal board is pretty fluid from night to night, you know, going to the music store and buying something, and pulling something else out. But I enjoyed using the OCD overdrive on a couple of things on the album.

What’s the speaker configuration you’re using?

Two cabinets with four 10-inch speakers.

You have a legion of fans who do everything they can to cop your sound. They’re buying your signature bass, they’re using your preamp, your DR strings, studying your records, learning your attack, etc. What is a component of your sound that might not be as obvious as all of that?

The fullness of the sound is important. Meaning, a lot of people get drawn to the high-end of my sound, but it’s really important that you support the band with the low end, so a lot of guys miss that. But I think the most important thing is the rhythm, really making sure that everything you play is rhythmically in there, and that it’s funky and it’s driving and it has meaning, you know?

Here’s a question that’s not music-related. You’re a basketball fan, right?

Yes.

If you could pick your Dream Team out of all the guys that ever played the game, who would be your starting five?

Starting five… I’d start with Magic at the point. I would have Kareem. I would have Oscar Robertson at small forward.

Oscar Robertson… the Cincinnati Royals I think?

Cincinnati Royals and Milwaukee Bucks.

Right.

He averaged a triple-double for his whole career. I would have LeBron. And my only problem I would have at the power point is telling Kobe that he might have to come off the bench, because he’s playing the two guard.

So LeBron makes the Dream Team?

Lebron would make the Dream Team, man, especially with Magic and Oscar Robertson, because they were winners, they knew how to do it. He would learn. I mean he’s already learned now, he already won, but can you imagine those guys? Whew.

Yeah, that would be quite a team.

Whew.

Of course I have to ask you a question about Luther Vandross. You were such a major part of so many of his great records, I don’t even know if people realize how big a part of them you were. Why, in your opinion, did the two of you work so well together? What was the essence of the collaboration?

Well, first of all, he taught me about singers. We were in Roberta Flack’s band; I was 18 or 19 years old. He would play me music of singers, and I was kind of like, yeah, yeah, whatever man, I’m a musician, you know? Singers are just the people in the front of the band entertaining the audience while the musicians do all the hard work. And Luther was like, oh no. [laughs]. He was like, we’re gonna change your perspective on that right now.

So he would play me Aretha Franklin records, Dionne Warwick, Donny Hathaway, and really break it down to me what they were doing, what made what they were doing special. And so I really learned how to think like he did. And when we started making records together a couple of years later, I really knew what he needed, and I really knew how to communicate that to musicians. So I think we worked really well together because I could sometimes interpret for him. I mean, he was very articulate, but he would say stuff like, “The bass drum doesn’t sound right”, and I’d say, “Well what do you need it to sound like?” He’d say “I need it to sound like my refrigerator door when it closes.” Which is clear, so I could tell the engineer he needed to boost this frequency and cut that frequency. So I think I learned how to think like Luther.

Kind of like a musical translator.

Exactly. And then I also learned what sounded good underneath him, because I knew the records that he liked. I knew all of his references because he had taught them to me. So I knew to try to make a contemporary version of this Aretha sound, or this Burt Bacharach sound, or this Donny Hathaway sound. I think we were kind of vibrating on the same frequency.

How about the songwriting, did you have a routine with him?

The first song we wrote together was for Aretha. Clive Davis called him, because Clive knew Luther was a fan of Aretha, and asked him if he would like to produce her. So Luther said to me, “Write me something uptempo for Aretha”. And I said, “Well, I’m really a jazz guy, you know”. He said, “Screw all that man, just write me the song, and let me know when you’ve got something.” So I put together a track for him, I did it on my four track Tascam, and I gave him the cassette. And he wrote to the cassette, he drove around with that cassette in his car writing lyrics and a melody. He’d call me up and sing me what he was thinking and I’d go, “Wow, that’s great.” As a matter of fact he was so excited about “Jump To It” he would tell me to get ready to have a hit, the thing is gonna be a smash. So it was very cool, and that became our routine. I would give him cassettes of things that I was working on and he would just drive around. Sometimes he’d put me in the car while he drove so he could bounce the ideas off of me, it went back and forth like that. The car played a lot of influence, you know what I mean? It’s the place where there are no distractions and you focus on the music. That’s still where I listen to my music a lot.

Speaking of you guys with Roberta Flack, I have her old Live And More album that you’re both on.

Ahhh! [laughs]

That’s one of my favorite albums, ever, man.

Yeah, that was a great experience for me. I didn’t want to play in her band because I was like 19, and the idea of playing those ballads wasn’t very appealing to me. But she cornered me on 48th street, she was riding a bicycle. She said, “You haven’t returned my phone calls, are you gonna do this tour?” I couldn’t say no to her face.

So I ended up doing the tour, and it became a great experience for me. I learned about how to play a ballad. I learned about how to use space. And Luther and I ended up meeting each other on that tour. So I’m glad she showed up on her bicycle.

Rick Suchow: Bass

marcus miller (august 2012)

Rick Suchow - Marcus Miller: Bass Musician Magazine

(Aug 1, 2012)